- TOP >

- FEATURE ARTICLES >

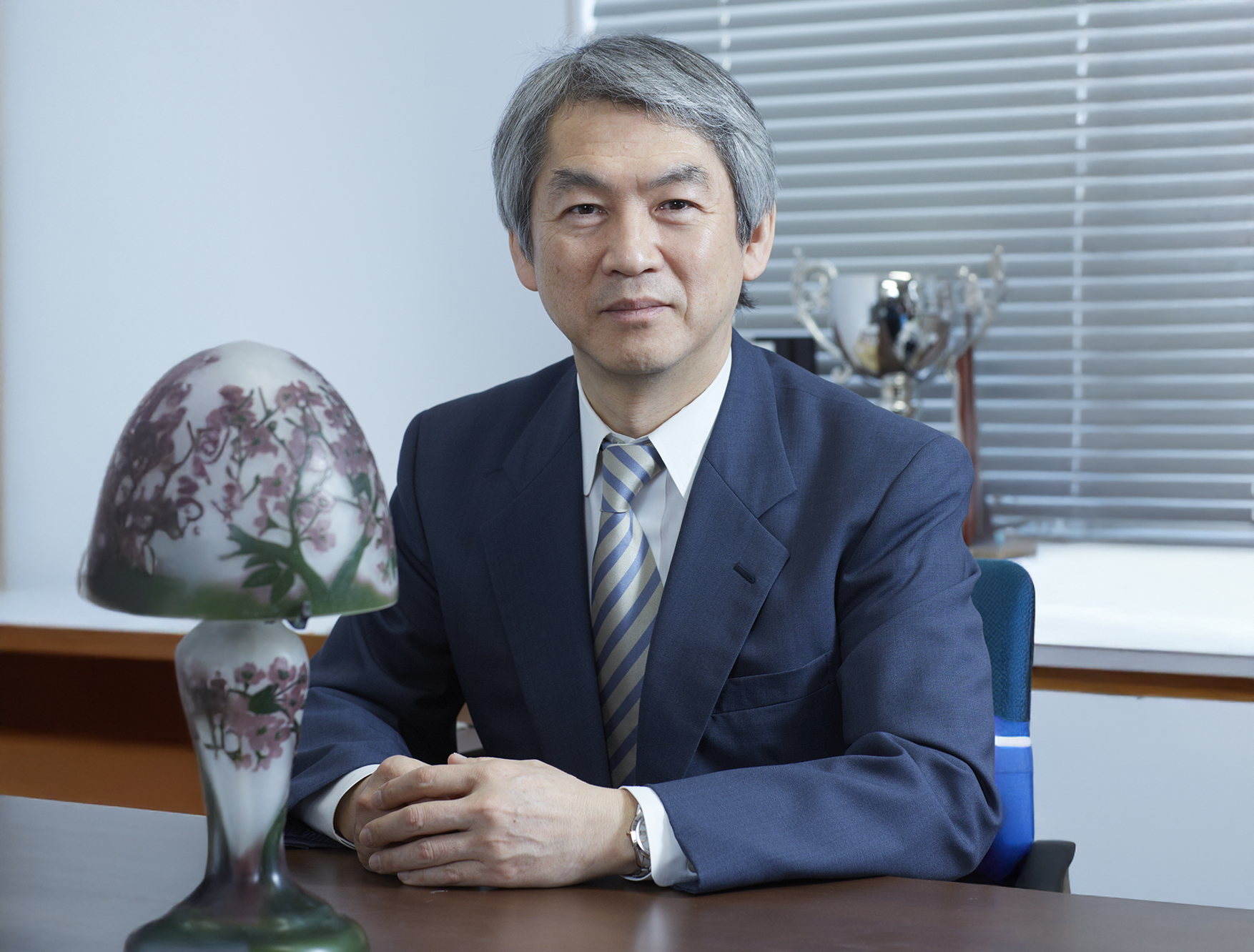

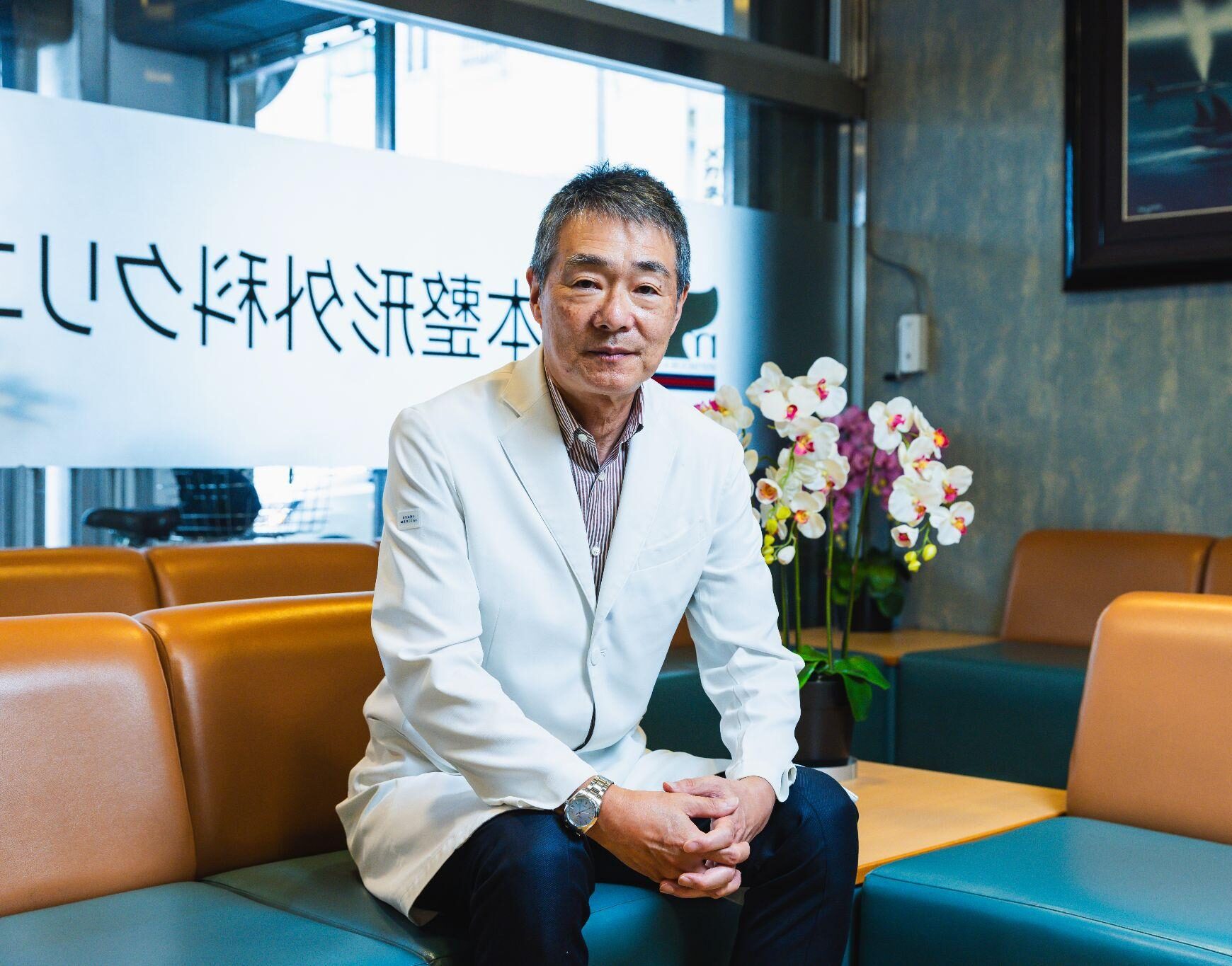

- Ko Masumoto

“Hard work always pays off. If it doesn’t, you haven’t worked hard enough.”

Ko Masumoto

Director

Masumoto Orthopaedic Clinic, Keiyū-Kai Medical Corporation

Website:http://www.masumoto-seikei.com/

Surgeon specializing in sports medicine. Team doctor for multiple professional teams, including the Yomiuri Giants.

- TOP >

- FEATURE ARTICLES >

- Ko Masumoto

The Experience That Set Me on My Path

I decided to become an orthopedic surgeon—specifically, a sports orthopedist—because of an experience I had in high school. At the time, I was chasing a dream shared by countless young athletes: to compete in the Inter-High School Championships, the pinnacle of high school sports. Our team advanced steadily through the regional qualifiers. Then, just three days before the Kanto tournament, the final step before nationals, I suffered a severe ankle sprain.

All I wanted was to play. Pain didn’t matter. But the team doctor, a highly respected physician, forbade me from competing. Back then, the idea was simple: if you’re injured, you rest. No exceptions. For a serious athlete, that logic was unbearable. Of course, if an injury risked long-term damage, rest made sense. But I couldn’t help wondering: shouldn’t there be treatment options to reduce pain temporarily and allow athletes to compete safely? Shouldn’t a doctor be able to support a player’s will to take the court? That question stayed with me.

Although I had to sit out that tournament, I eventually recovered and made it to the Inter-High that summer, fulfilling my goal. But I often think how easily my playing career might have ended at the prefectural level if I hadn’t recovered in time. That experience convinced me to become a doctor who helps athletes return to competition, not just recover for daily life.

A Different Goal for Healing

What sets sports orthopedics apart from general orthopedics is the goal. Regular orthopedic medicine aims to restore a patient’s ability to function in daily life. Sports orthopedics, on the other hand, must determine when and how an athlete can safely return to play.

My priority is always the athlete’s wish to compete. This approach often leads to higher patient satisfaction because treatment aligns with their personal goals. Take, for example, American football linemen. They battle on the front lines, colliding head-on with their opponents. They’re tough—so tough that minor fractures barely faze them. Their position demands strength, not endurance. Understanding this, I might allow participation even with certain fractures, provided the long-term risk is minimal.

That might sound reckless, but for professional athletes, missing a game can mean losing their place on the team or even altering their career. As long as the risks are low and fully understood, I believe it’s reasonable to let them compete. To practice this kind of medicine, a doctor must thoroughly understand the nature of each sport and the risks specific to each injury. The key is open communication and shared decision-making with the athlete.

When Told “Impossible,” I Work Harder

Many of my patients come after being told elsewhere, “You can’t play.” That’s when I get fired up. When someone says it’s impossible, I think, “then let me find a way.”

Most of these athletes are in junior high or high school. When I hear later that one of them made it onto the field safely, I feel genuine joy. Their words—“Thanks to you, doctor, I was able to play!”—are the best reward I could ask for.

When that happens, word spreads quickly through the local school networks. Pediatricians, internists, and other orthopedic specialists begin referring similar cases. Each time, I’m reminded that I’ve reached the field I dreamed of decades ago: being a doctor who treats athletes so they can compete.

The Essentials of My Practice

Let me explain how I approach treatment.

First, I talk extensively with each patient to understand their condition and circumstances. I explain the treatment options, the potential to play, and the risks involved. When the patient is a minor, I discuss the same points with their parents. Ultimately, the decision to proceed lies with the patient, once we both reach mutual understanding.

Second, understanding the sport itself is vital. At my clinic, more than ten physical therapists assist with treatment; all of them have athletic experience. They visit games and practices regularly to deepen their understanding of each sport. Even if a clinician has no athletic background, it’s possible to provide care—but knowing the nuances of a sport allows for more practical, tailored treatment.

That said, it’s equally important not to push too far. For growing children, overexertion can lead to bone or joint deformities. When I judge that the risks outweigh the benefits, I stop the athlete from playing, even if they plead through tears. Making those calls requires deep expertise and experience.

Sports orthopedics goes beyond treating injuries. It’s about understanding each athlete’s situation, their dreams, and the stories behind them. Then, we help them find the best path forward. I take pride in every one of those decisions.

The satisfaction I’ve gained in my career comes from staying true to the ideals I formed in my youth. To the next generation of doctors and medical students, I say: never forget the reason you chose medicine. Keep working, keep learning, and use your skills to bring happiness to others.