- TOP >

- FEATURE ARTICLES >

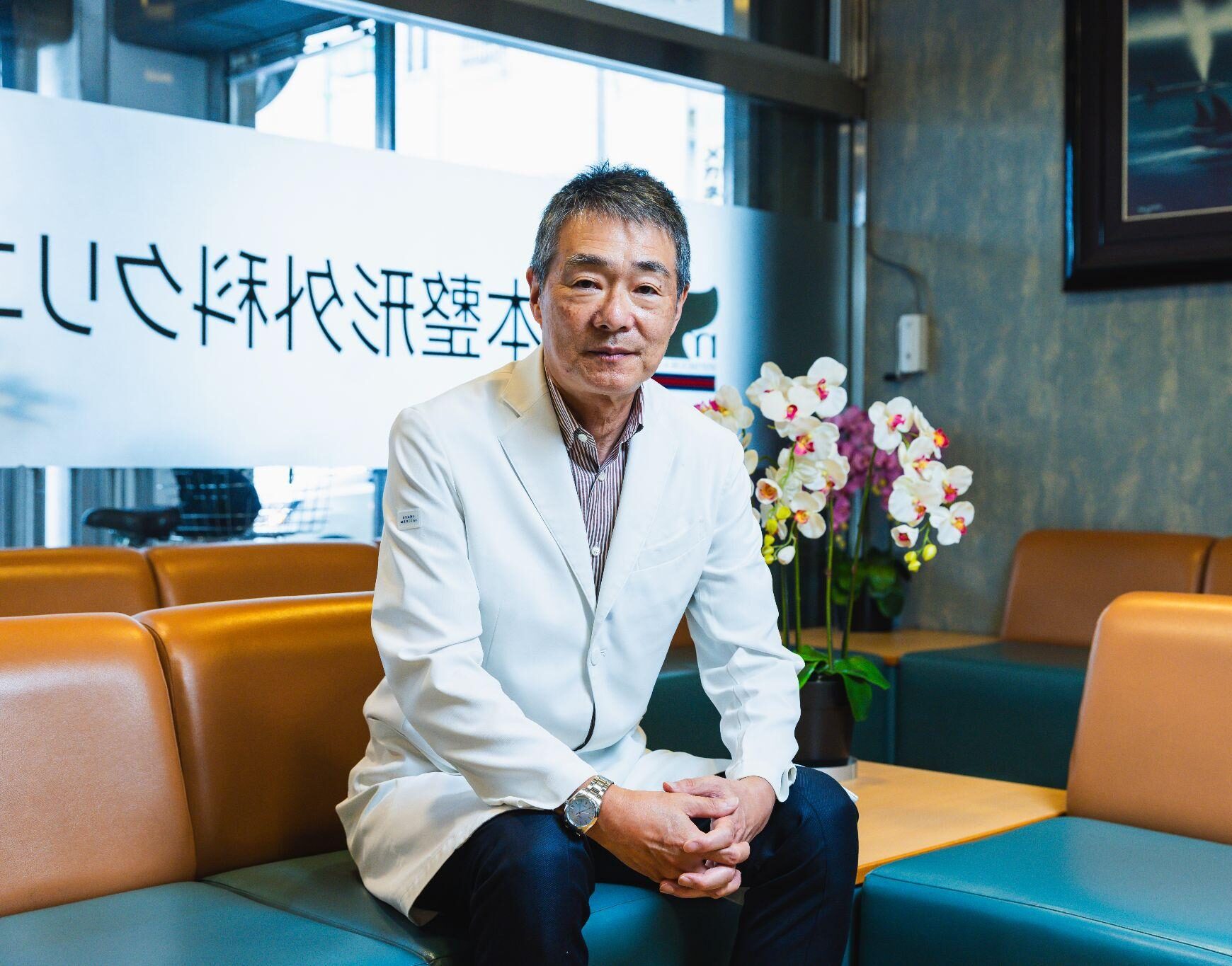

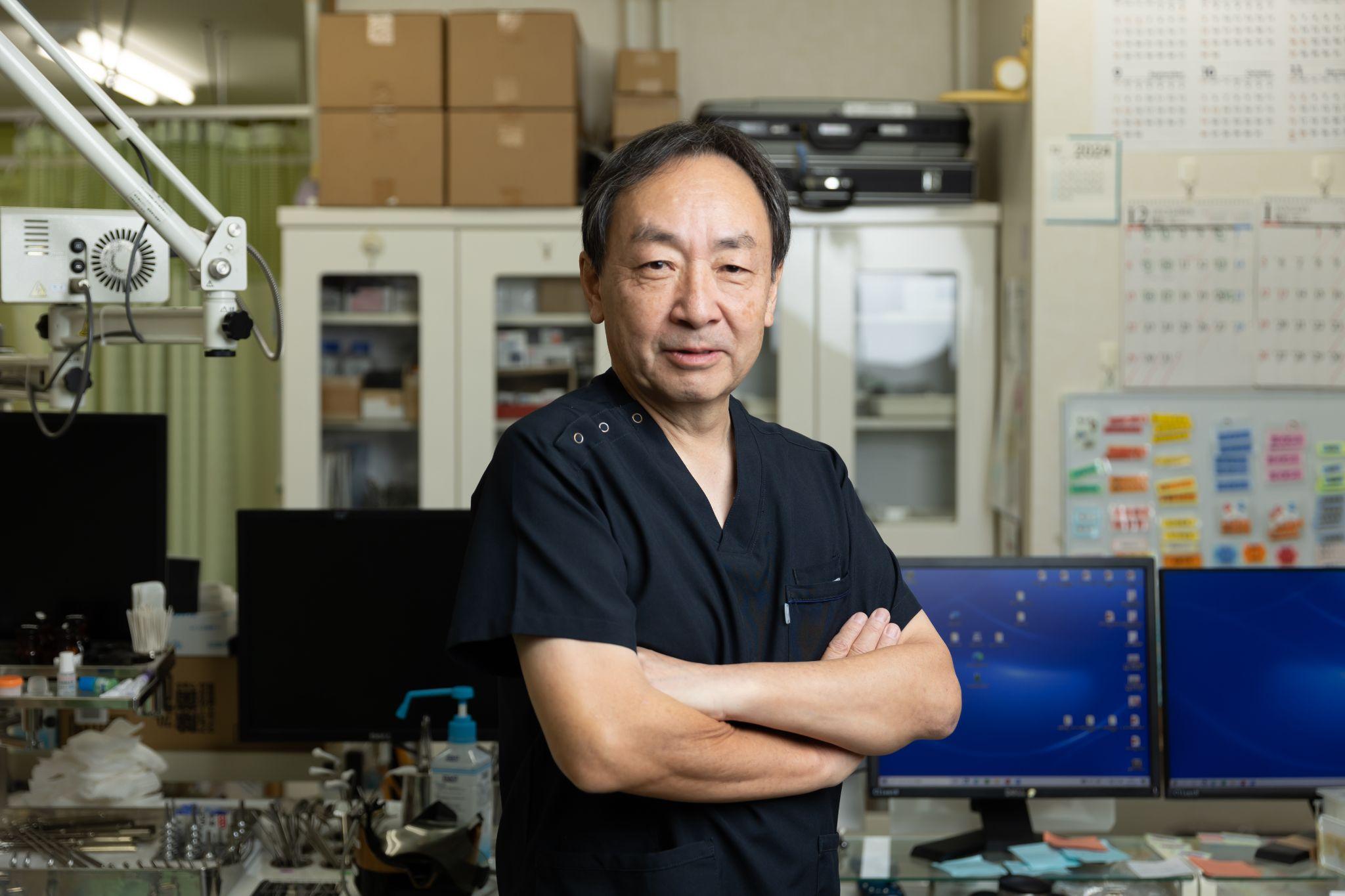

- Kazutaka Yamada

“Do tomorrow what can be done tomorrow.”

Kazutaka Yamada

Director

ENA Ladies Clinic, Kitan-Kai Medical Corporation

Website:https://ena-lc.com/

Obstetrician-gynecologist dedicated to enhancing pregnancy and childbirth in Japan through advanced care and advocacy.

- TOP >

- FEATURE ARTICLES >

- Kazutaka Yamada

If Not Me, Then Who?

I didn’t come from a family of doctors, yet even as a child, I somehow knew I would become one—and more specifically, an obstetrician-gynecologist. When I entered medical school, specializing in obstetrics and gynecology felt like a natural path.

I’ve always believed that life isn’t something doctors “save,” but something sustained by the innate vitality of human beings themselves. I’ve been involved in countless cases where both mothers and infants have survived against great odds, but beneath those outcomes lies the strength of their own life force. Our role as physicians is simply to support that force. In this sense, my view of medicine has always differed slightly from the surgical mindset that sees a doctor’s skill as the decisive factor in saving a life.

After graduating from Shiga University of Medical Science, I joined the Perinatal Medical Center, which provides care for high-risk pregnancies and critically ill mothers and newborns. The smallest baby I ever delivered weighed less than 300 grams, born severely premature. I also treated fetuses with congenital heart defects and mothers suffering from life-threatening complications such as massive hemorrhage or preeclampsia. For more than a decade, I’ve worked on the front lines of obstetric emergency care, doing everything possible to safeguard both mother and child.

In Japan, roughly three to five mothers die for every 100,000 births, and fewer than one in 1,000 newborns fail to survive. Perinatal centers are the hubs that make those numbers possible. These facilities are capable of responding to sudden crises and providing highly specialized care.

Rethinking the Value of Birth in a Demanding Profession

At major perinatal centers, more than a thousand deliveries may take place in a single year. It’s not unusual to attend five or six births in one day. Over time, you find even as one baby is being born, your mind has already shifted to the next delivery. That’s the reality of the job.

But somewhere along the way, I realized I and many of my colleagues, had started to see expectant mothers and their fetuses less as people and more as “cases.” Of course, objectivity is essential for accuracy and safety. Yet I began to wonder whether, in that process, we were losing sight of the fact that each birth is one of the most meaningful moments in a person’s life.

The Patient Who Changed My Mind

My perspective shifted during my years in graduate school. A pregnant patient I was caring for had been hospitalized for induced labor. Despite our efforts, her delivery wasn’t progressing. Wanting to help her finish giving birth during my shift, I tried to adjust the timing.

She stopped me. “It feels like you’re treating my childbirth lightly,” she said, asking that I step aside.

I thought I was doing my best for her, but in truth, I had started to see her as a case to manage. That experience forced me to confront how little I’d prioritized her feelings. It was a turning point that reshaped how I approach childbirth and my patients ever since.

Elevating the Value of Pregnancy, Birth, and Childrearing

What is the ideal birth? To me, it’s one that matches the vision a mother and her family have for it. Whether it’s the environment, delivery method, or how they spend the days before and after, the role of obstetric care is to help make that vision a reality.

To pursue that ideal, I founded "ENA Ladies Clinic" in Osaka’s Miyakojima Ward in 2022. My goal is clear: to raise the social and emotional value of pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing.

Medical intervention can only go so far. To fulfill a mother’s wishes, care must be flexible and varied. Many women today request painless delivery, but most hospitals that offer it limit the procedure to certain hours or scheduled births; these restrictions prioritize institutional convenience over patient choice.

At ENA, we accept every situation as it comes. We don’t refuse care based on hospital convenience. Even when we can't meet a mother's wishes exactly, we work together to get as close as possible.

An Extraordinary Space Within the Everyday

That philosophy extends to the clinic’s design. The interior evokes the calm of a traditional Japanese ryokan, with tall floral arrangements, bamboo furnishings, and carefully curated tableware and meals. I wanted mothers to experience a touch of the extraordinary within the everyday.

In recent years, postpartum care has become a major topic in Japan. Sadly, the leading cause of death among new mothers here is suicide during the childrearing period—a stark sign that support systems remain inadequate. To address this, we’ve expanded postpartum services and will open a dedicated postpartum care center in April 2025. Our clinic already serves as a backup facility for local postpartum hotels, offering medical and emotional support.

Building a Society That Values Birth

It’s encouraging that more companies are beginning to take women’s health seriously. Some major corporations in entertainment and retail have introduced subsidies for birth control prescriptions, helping employees balance health and career. Our clinic has also received more requests from companies and daycare centers to host seminars on reproductive and maternal health.

When corporations actively support women through different life stages, they generate goodwill and tangible economic benefits. I believe partnerships between medicine and industry can shift social consciousness. We aim to be part of that change.

The Heart of Japan’s Declining Birthrate Problem

Japan’s declining birthrate, I believe, stems from a loss of perceived value in pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing. The high cost of childbirth certainly plays a role, but many couples hesitate to have children because they fear their standard of living, or even their sense of self-worth, will decline.

Middle-income families, in particular, face growing pressure to maintain their lifestyle as take-home pay decreases. There is also a striking mismatch in how society values childbirth itself. In Japan, the average cost of a delivery is estimated at around 1.1 million yen (roughly $7,000), whereas in the U.S., vaginal births can cost 3 to 4 million yen, and cesarean sections up to 10 million yen. Weddings here average 3 million yen, yet the act of giving birth, a moment that literally risks a mother’s life, is undervalued and often discussed in terms of how to make it cheaper.

Decades ago, when Japan was far less affluent, childbirth was still celebrated as a social and familial joy. As a professional in perinatal medicine, I strongly believe that now is the time for society to reexamine the worth we assign to pregnancy, birth, and parenting.

That’s why I’ve devoted my work to raising that value—through every delivery, every patient interaction, and every step toward a society that truly genuinely honors the beginnings of life.